- Introduction

- Fields of Study

- 2.1 Defining Evolution

2.1.1 Positions in Islam and Evolution

2.2 Focus of this Puzzle

2.2.1 Seyyed Hossein Nasr

2.2.2 Shoaib Malik

2.2.3 Nidhal Guessoum

- 2.1 Defining Evolution

- Discussion

- Conclusion

1. Introduction

Islam and science is a relatively nascent field. With the steady rise of publications in the past three decades, a handful of thinkers have suggested various proposals on how to understand the relationship between the two domains, with the theory of evolution being one of the most, if not the most, important issue in the budding field of Islam and science (Guessoum 2016; Malik 2021). Using the theory of evolution as a case study, this article reviews the proposals of three thinkers – Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Shoaib Ahmed Malik, and Nidhal Guessoum. This focused analysis reveals that the theological/metaphysical presuppositions of each thinker significantly affect their approaches and conclusions when looking at the relationship between Islam and evolution. Let us define what we mean by evolution before we get into the puzzle.

2. Fields of Study

2.1 Defining Evolution

The theory of evolution, at least the Neo-Darwinian interpretation, boils down to three propositions:

- Deep time – the earth is significantly older than what we traditionally held; our current estimates reveal that our earth is around 4.6 billion years old.

- Common ancestry – all biological organisms are connected through a long bio-historical lineage in a family tree.

- Mechanisms – the primary driving forces of evolution are natural selection and random mutations.

Historically, the Abrahamic civilisations believed the earth was really young, between 6,000 to 10,000 years old. However, with advances in physics, radioactivity in particular, our current estimates reveal that earth was created around 4.6 billion years ago while our universe was created 14.6 billion years ago, which is significantly different to our previously-held beliefs (Young and Stearley 2008).

The second principle stands also in stark contrast to our prior conceptions. Previously, the Great Chain of Being was a dominant worldview in Abrahamic communities (Lovejoy 2009). This framework viewed the world in terms of fixed ontological settings, like rungs of a ladder, with increasing perfection as you go up. Starting from the most basic level, minerals only exist as simplistic matter. Plants are higher on the chain due to increased complexity; they can reproduce unlike minerals. Animals are more perfect than plants because of increased maneuverability. Humans are higher up in the chain than plants and animals because of their advanced intelligence. However, the chain does not stop there and is successively followed by many metaphysical entities, e.g. angels and heaven, with God being right at the top due to His absolute perfection. Each part of the chain is directly created by God and are not physically interconnected with one another as opposed to an evolutionary understanding (Malik 2021, 155-176).

This worldview was challenged in the late eighteenth century. Jean Baptiste Lamarck was one of the first modern proponents of biological ancestry. He believed that all biological life was interconnected through a historical lineage. Latter entities were descendants of biological ancestors. However, he did not believe in common ancestry. His interpretation of the history of life is best depicted as blades of grass. In his interpretation, life spontaneously arises several times throughout the ages, which entails that there were several successive yet independent evolutionary pathways that progressed in parallel. Lamarck believed that humans were the highest and the inevitable peak point of evolutionary pathways. Other animals and plants that we see today are younger evolutionary pathways in relation to the evolutionary timeline of humans. Eventually, all other timelines will lead to the development of human beings (Corsi 1988).

Charles Darwin, the man famously known for evolution as we know it today, agreed with Lamarck that life evolved. However, unlike Lamarck, he argued for common ancestry. In contrast to the blades of grass metaphor, however, Darwin viewed evolution like a tree, which has a trunk, several branches, and twigs. All life was interconnected and not separated due to parallel pathways initiated by different and separate origins of life (Ruse 1999).

The third principle is about the mechanisms of evolution. What makes evolution tick? When Darwin first proposed his theory of evolution, he had moderate success with convincing the scientific community about ancestry, but he struggled to convince it of the plausibility of his preferred mechanism: natural selection. In essence, natural selection explains that species carrying conducive biological traits, which are inherited from external environments and aid in competitive survival, tend to reproduce successfully. But with the constant flux found in nature, those pressures also vary through time and space. A branching of species (populations) occurs because certain members of the parent species diverge from the original group and adapt to different localities due to different environmental pressures (Stearns and Hoekstra 2005).

However, Darwin did not possess a clear concept of heredity and variation – nobody did at the time (Müller-Wille and Rheinberger 2012). Such a concept was important because it would show exactly how differences and similarities in successive generations between and within species could be explained. Since the concept of the gene was not established in Darwin’s time, the validity of natural selection as a causal mechanism of evolution remained questionable, with many competing theories until the 1930s, which is when Mendelian genetics rose to the surface. Mendelian genetics illustrated how genes and mutations possessed significant explanatory value in that they could explain heredity and variation. It was eventually merged with natural selection to form what is now known as Neo-Darwinism or the Modern Synthesis (Bowler 2015). In this new framework, there is a constant dialectic tension between genes and the environment whereby chance-like events, i.e. no long-term purposes in mind, can equally lead to positive, negative, or neutral traits to be expressed. Such chance-like events can be external, e.g., natural disasters, or internal, e.g. random genetic mutations. Putting all this together, the biodiversity that we have identified is the result of several successive generations of heredity, variations, and adaptations across deep time (Futuyma and Kirkpatrick 2017). In this account, and in contrast to Lamarck, humans are but one accidental product of a long and complicated evolutionary pathway.

Turning to the 21st century, there is now debate about whether the Modern Synthesis is indeed adequate to explain all of life’s nooks and crannies. Some believe that the causal efficacy and/or sufficiency of natural selection and random mutation need to be questioned. The Extended Evolutionary Synthesis has gained momentum as a possible alternative to or, rather, a natural transformation of the Modern Synthesis (Pigliucci and Müller 2010). This position advocates for the inclusion of other causal mechanisms such as niche generation or epigenetics, among others. Neo-Darwinists naturally disagree. Whether the Modern Synthesis will remain, be transformed, or be left behind remains an open question (Laland et al. 2014; Wray et al. 2014).

2.1.1 Positions in Islam and Evolution

The question of the compatibility between Islam and evolution is still a very hotly debated topic (Guessoum 2016). Muslim thinkers have generated ideas which fall all over the spectrum. In a recent work, Malik divided thinkers into four different positions that are differentiated by what they accept or reject as part of common ancestry (Malik 2021). Table 1 captures the gist of these positions.

Position | Are non-humans a product of evolution? | Are humans a product of evolution? | Is Adam a product of evolution? |

Creationism | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ |

Human Exceptionalism (HE) | ✓ | ✘ | ✘ |

Adamic Exceptionalism (AE)[1] | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ |

No exceptions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Creationism and the no exceptions camp are complete opposites of one another. Creationism is the stance that common ancestry is false in its entirety, while the no exceptions camp believes the contrary, and thus permits no special pleading for Adam and humans. Human exceptionalism is the position that common ancestry is true except for human beings. In this perspective, Adam is considered the first member of humankind, and since he was created miraculously, him and his entire progeny are exempted from the process of evolution. This position is held by Yasir Qadhi and Nazir Khan (2018) and they reconcile it as follows. For them, God miraculously created Adam and Eve at the expected moment when humans were supposed to spring forth through evolutionary pressures. Subsequently, the fossil record appears like a seamless continuation of evolutionary processes that includes human history when looked at scientifically. From a theological lens, however, Adam and Eve’s miraculous creations were real metaphysical events as depicted in Islamic scripture. For Qadhi and Khan (2018), this does not lead to a conflict as such, as these two ideas occupy different disciplinary modalities: “The occurrence of such a scenario is theologically plausible and would be impossible to disprove empirically since it is a metaphysical assertion.”

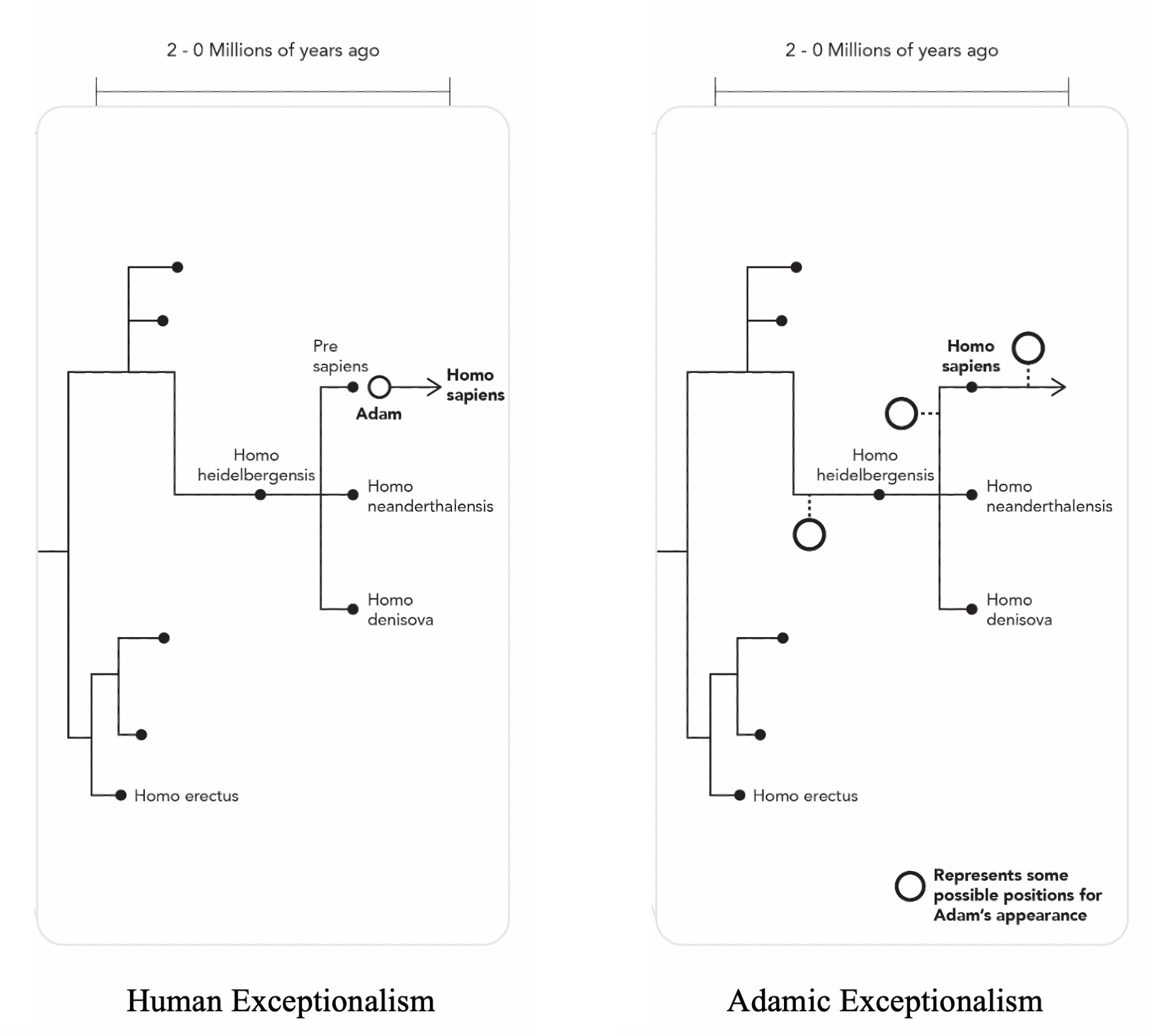

Figure 1 – Differences between HE and AE.

Figure 1 – Differences between HE and AE.

Adamic exceptionalism agrees with human exceptionalism insofar that Adam’s miraculous creation is retained. However, rather than assuming that Adam is the first member of humankind, Adamic exceptionalism states that Adam and Eve are isolated miracles, and there is nothing in Islamic scripture that explicitly and clearly suggests that they were the first members of humankind. This leaves open the hermeneutic possibility and compatibility of there being pre/co-Adamic humans on earth when Adam was created miraculously, which does not contradict Islamic scripture. This position’s validity is argued by David Solomon Jalajel (2009; 2018). The differences between human exceptionalism and Adamic exceptionalism are visually depicted in Figure 1.

2.2 Focus of this Puzzle

This theological puzzle will ask a broad and yet more fundamental question: Is evolution even possible in Islamic thought? On the face of it, the answer seems very obvious. If Muslims believe in an all-powerful God, then why would evolution not be possible? The answer to this question depends on the background metaphysical presuppositions that each thinker occupies.

Islam, just like any religion, has a rich history with many different theological and philosophical schools of thought, e.g. Ashʿarism, Māturīdism, Atharism, Avicennism, Muʿtazilism, Sufism, and anti-traditionalism,[1] among others (Winters 2008; Jackson 2009; Schmidtke 2014). Accordingly, one can find many metaphysical perspectives under the umbrella of Islam. Thinkers looking into the field of Islam and evolution naturally rely on and utilise their adopted metaphysical paradigms when evaluating the relationship between the two. This, in turn, leads to difference of opinions in the creationism-evolution debate.

This theological puzzle will review the presuppositions of three different thinkers, Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Shoaib Ahmed Malik, and Nidhal Guessoum. They are specifically chosen because of their very different metaphysical systems, which allows for a fruitful comparison. Doing so will reveal how these lead to differences of opinions in the discourse of evolution. Of course, each thinker may have other kinds of arguments at their disposal for their respective positions, e.g. scientific or hermeneutic, but the focus of this puzzle is primarily on the metaphysical principles that are part of their modus operandi. When needed, their non-metaphysical commitments will be highlighted.

2.2.1 Seyyed Hossein Nasr

Nasr is an Iranian-American physicist-turned-philosopher. He is a well-known and a long-time critic of evolution and does not shy away from his creationist stance. His Neo-platonic perspective can be found in many different places, but his integrated argument against evolution is presented most recently in an article called On the Question of Biological Origins, which will be used for presenting his perspective. He seems to have two distinctive metaphysical ideas that he thinks warrant a case for rejecting evolution.[2]

First, he believes that Western society[3] has lost its understanding of ultimate intelligible forms (Nasr 2006, 183):

A triangle is a triangle, and nothing evolves into a triangle; until a triangle becomes a triangle, it is not a triangle. So if we have three loose lines that gradually meet, even if there is one micron of separation, that is not a triangle. Only a triangle is a triangle. And life forms also have a finality of their own.

Now, the traditional idea of form (morphos) has lost its status in both Western philosophy and Western science. The only thing that survives is mathematical forms which themselves are abstracted forms. But concrete forms were thrown out of science by Galileo and Descartes. Once you quantify science and say that science is the quantified explanation of things, you can no longer deal with forms which deal with the quality of things. The form of an orange—you cannot study it in modern physics. In fact, what you do is to study the weight of the orange, its sphericity; or in chemistry the amount of acid in its juice, in biology its molecular structure. So what happened to the orange? You do not study that.

Second, Nasr believes that God’s involvement with the world seems to have diminished with the theory of evolution (Nasr 2006, 184):

In modern evolutionary theory, the vertical axis, which would explain why certain forms appear in the material world, has been horizontalized and therefore it is only through the matrix of time and matter that modern science understands the genesis of anything including living forms.

The conjunction of these two principles – loss of forms and rejection of the vertical axis – lends him to believe that evolution isn’t possible, as evolution considers species as transient temporal affairs that undermine the eternality of the archetypes and thus the involvement or the role of God in the process (Nasr 2006, 191):

And if God does not know the ant in the metaphysical sense, because the ant has not essence to be known in a permanent manner but is simply part of the temporal flow and not the result of His creative act, how can He be God from an Islamic perspective? …

If God has knowledge of the ant, the ant must have a kind of archetypal reality in the ‘mind’ of God, in the Divine Intellect. To say that there is no such creature whose essence is the reality of the ant, that the ant is simply a stage in evolutionary transformation, is to take a certain part of temporal sequence and call it an ant; before that it was something else and it will evolve into something else … This is itself a very strong argument against evolutionism from the Islamic point of view.[4]

To be clear, his perspective doesn’t entail a denial of microevolution (change within species), but it is only macroevolution (change across species) that is the problem (Nasr 2006, 184–185):

There is the possibility of micro-evolution, but not of macro-evolution. Now micro-evolution is still within the possibilities of the archetype or form of a particular being in the philosophical sense in the same way that you and I are human beings, and the Chinese and the Japanese are also human beings. Our eyes are one way; their eyes are another way. If we migrate to Zimbabwe, our skin grows darker; if we go to Sweden, it would grow a bit lighter. But we are all within the possibilities of the human form. That kind of micro-evolution is possible. Flies can become a bit bigger and when there is a certain kind of light, plants can do this and that, and this is mistaken by some for change of species. That is not change of species; that is ‘evolution’ within a single species. Each species has a width, a range, a reality greater than a particular individual in that species. And so other individuals can appear in that species with other characteristics and even change according to environmental conditions, without one species becoming another.

In short, Nasr does not have a problem with changes within species, as they seem to be accidental differences rather than essential ones, and thus don’t undermine the archetypes. However, he finds changes across species to be problematic because he believes that each Neo-platonic essence of form corresponds to a natural species; and since intelligible forms are immutable, so too are the material manifestations of those forms. Therefore, evolution is completely unworkable given the importance of Neo-platonic forms, God’s role in expressing those forms in the created world, and the linear correspondence between the two. For these reasons, Nasr is squarely a creationist.[5]

2.2.2 Shoaib Malik

Malik is a Pakistani chemical engineer-turned-philosopher. He adopts and applies Ashʿarite theology, particularly the thoughts of the classical Muslim theologian Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī, to the question of Islam’s compatibility with evolution. For Malik, the discussion starts with understanding the nature and attributes of God, the nature of creation, and the divine action model that connects them. Once that framework is established, the various possibilities that are available in the literature can be evaluated through it. Accordingly, a summary of Ashʿarite theology will be helpful here.

Ashʿarite theology is committed to the following positions (Malik 2021, 179-211):

- God as the volitional, necessary being

- God’s omnipotence is defined by what is logically or metaphysically possible

- Occasionalism as its divine action model

- The radical contingency of creation

Proponents of the Ashʿarite school divide all that exists into what is necessary and contingent. God is the sole necessary being while everything is radically contingent. Anything that does exist is either contingent or necessary. Given that all of creation’s constituents are contingent, they must be grounded in a necessary being. Furthermore, God is a volitional being who can choose to create whatever He so wishes or not, e.g. physical entities, including the universe, humans, and particles, among others, and (supernatural) realities, including angels, demons, heaven, and hell, among others. This particular point came out of the interactions that Ashʿarites had with Hellenic philosophers, who Ashʿarites critiqued because they believed that creation occurred non-volitionally (Al-Ghazālī 2000). The Ashʿarites also stress that God is omniscient, as his knowledge knows no bounds. Furthermore, the Ashʿarites strongly advocate for his omnipotence. They believe that God’s creative powers are not curtailed by any moral or physical necessities, and are only governed by some eternal norms as expressed in metaphysical or logical truths. In other words, God can only create what is metaphysically or logically possible. In this kind of framework, it is possible for God to create worlds that are totally chaotic with no laws at all and worlds with different laws to ours. He can equally create worlds that do not look designed and are simpler than ours or even more complex than our world. Furthermore, God can even alter natural regularities in our current world to create momentary local events. Accordingly, Ashʿarites have no problem with accepting miracles as genuine possibilities in the actual world. God could very well split the sea before Moses, turn his staff into a snake, and split the moon. Moreover, the Ashʿarites believed in an occasionalist divine action model in which God is the sole efficient cause of all phenomena. No created being can have ontological autonomy outside or beyond God’s power. Using animations as an analogy, God wills each moment to define every single detail from one timeframe to another (Jackson 2009; Koca 2020; Malik 2021, 177-264).

Given this framework, Malik then evaluates the metaphysical possibility and scriptural compatibility of Neo-Darwinism and Islam, which he takes for granted while noting the debate of other causal mechanisms (Malik 2021, 21-65). He concludes that God can execute any one of the aforementioned scenarios: creationism, human exceptionalism, Adamic exceptionalism, and no exceptions. In other words, Malik (2021, 204) accepts the metaphysical possibility of God creating through creationism and evolution. However, he also maintains that creationism, human exceptionalism, and Adamic exceptionalism are scripturally compatible, as scripture neither affirms nor denies these realities; but he rejects the no exceptions camp, as he is committed to the miraculous creations of Adam and Eve (Malik 2021, 296-337). Which one of the three position is the correct position is not a theological (creedal) matter, which is why Malik maintains a stance of theological non-commitment on the problem, but he admits that Adamic exceptionalism is the closest alignment one can get with evolution (Malik 2021, 338-348).

2.2.3 Nidhal Guessoum

Guessoum is an Algerian astronomer. His metaphysical scheme is less explicit than the previous two thinkers. However, this does not mean that it is not discernible. He largely takes his inspiration from the Hellenic philosopher Averroes, who Guessoum believes can provide guidance for modern day discussions, such as Islam and science. As a point of caution, Guessoum is very selective with what he finds relevant in Averroes’ framework for his narrative. Guessoum does not, for instance, engage or discuss Averroes’ metaphysics in his works. Of the ideas which Guessoum does find attractive in Averroes’ framework, the following quotation of Averroes is significant (quoted from Guessoum 2011, xxii):

We say: If the activity of ‘philosophy’ is nothing more than the study of existing beings, and the reflection on them as indications of the Artisan, inasmuch as they are products of art,

for beings only indicate the Artisan through our knowledge of the art in them, and the more perfect this knowledge is, the more perfect the knowledge of the Artisan becomes.

And if the Law has encouraged and urged reflection on beings, then it is clear that [any] activity [of the same kind] is either obligatory or recommended by the Law.

In other words, Guessoum à la Averroes believes that through doing science we can appreciate God’s artisanship, which in turn could also be seen as a form of bettering our understanding of God (Guessoum 2011a, xxi-xxiii):

Averroes is declaring any human activity, such as philosophy and science, to be at least commendable, if not obligatory, for the simple reason that it leads to greater knowledge and appreciation of God (the Artisan), through the study of His creation.

Subsequently, Guessoum believes science plays a very important role in determining what is and isn’t metaphysically possible, which ties in together with his wider principles.

Guessoum stresses that the world is ordered and contains physical laws that can be discovered by the mind (Bigliardi 2014, 161-162). For him, God does not interfere with the physical mechanisms and only interacts through the spirit, i.e. the mental connection with God (Bigliardi 2014, 176). To be sure, Guessoum believes that, while God is capable of interfering with the laws of nature, it wouldn’t make sense for Him to interfere with the laws He set out in the first place (Bigliardi 2014, 175):

… because He is omnipotent it does not mean that He is just going to violate His own laws. So I am not saying that God cannot; I am saying that God put together the laws so that things function in an orderly manner. Otherwise what is the point of putting together laws, and then doing whatever one wants every now and then? The world is ordered and harmonious; the Qurʾān itself emphasises that. On the contrary, God is saying ‘I am omnipotent but even I, omnipotent, put together laws by which creation proceeds, and I want you to follow laws, and I want you to be orderly, to follow the order.’

Accordingly, miracles, if understood as violations of laws, do not really occur according Guessoum (Bigliardi 2014, 175):

… putting together all these ideas of how to read the Qurʾān, how to understand the stories of the Prophets, what is the meaning of God’s order, what are the laws of God and nature etc., all of this for me rules out the idea of miracle as a violation of laws. Miracles are very lucky events, providence, coincidences.

Finally, Guessoum (2011, 271-324) states clearly that evolution (microevolution and macroevolution) is a fact, with humans being no exception, as there are multiple lines of evidence for this, though he is careful to note that there are non-Darwinian interpretations of the causal mechanisms.

Given the highlighted principles, laws and his full embrace of evolution, it is then no surprise to see that, in being consistent with his framework, Guessoum rejects miraculous readings of Adam and Eve (Guessoum 2011b). Accordingly, he does not admit the possibility of creationism, human exceptionalism, and Adamic exceptionalism, and thus squarely falls in the no exceptions camp.

3. Discussion

There are two observations that can be made given the brief reviews covered in the previous sections. First, there is a clear difference of approach. For lack of a better descriptor, Nasr and Malik adopt top-down approaches. In this approach, both base their method of analysis on higher-level commitments, namely God and his attributes. Nasr, in relying on a Neo-platonic framework, primarily focuses on forms or ideas in the mind of God. Malik focuses on God’s creative possibilities through the Ashʿarite framework. They then use these as their starting points to evaluate the possibility of evolution. By contrast, and provided that the distinction is permitted, Guessoum represents more of a bottom-up approach in which science is the starting point and thus given precedence. With the emphasis on science, he believes that the universe is a strictly lawful (and thus scientifically-governed) place in which miracles are not possible, and therefore he cannot accept anything but the no exceptions position.

If we entertain hypothetical engagements between these approaches, from Nasr and Malik’s perspectives, Guessoum’s position could be seen as metaphysically simplistic, as it is too preoccupied with the science, and possibly harbouring scientism (Malik 2021, 296-337). Guessoum could retort by claiming that Nasr and Malik’s stances are metaphysically extravagant and pure arm-chair speculations, and thus aren’t grounded by any scientific measure, and therefore contribute nothing substantive to the conversation (Guessoum 2011a, 321). With respect to Malik’s framework in particular, Guessoum does make it very clear that he has significant disagreements with Ashʿarism (Bigliardi 2014, 176).[6]

Second, even when thinkers adopt the same approach, they may radically disagree in their conclusions. Nasr and Malik adopt a top-down approach. However, Nasr argues that Neo-platonism cannot accept macroevolution, as it fundamentally collides with the idea of eternal forms or archetypes in the mind of God, and thus only accepts creationism. By contrast, Malik’s metaphysics is predicated on Ashʿarism, which accepts the reality of miracles and permits the metaphysical possibility of creationism and evolution (Neo-Darwinian or otherwise). However, he rejects the no exceptions camp due to scriptural references, thereby leaving open the possibilities of creationism, human exceptionalism, and Adamic exceptionalism. So, if evolution is scientifically robust, it would not undermine the Islamic faith and scripture.

From Nasr’s perspective, Malik’s framework could be seen as being too metaphysically permissive and negligent of the problem of forms as highlighted earlier. By contrast, Malik could suggest that Nasr’s position is too restrictive because, given God’s omnipotence, God can create any kind of forms, as everything in creation is radically contingent. Humans in this world were created with a specific form, but there is nothing stopping God from creating humans with a different essential nature altogether. Their respective counter responses will naturally fall back on their wider metaphysical commitments about the nature of God, His attributes, and divine action models.[7]

Collectively, these observations make it evident that one’s approach and metaphysical (and, of course, other kinds of) commitments affect how one navigates the discussion of Islam and evolution, and, depending on how those stances are addressed and what they are, they can lead to very different conclusions.

4. Conclusion

This theological puzzle attempted to answer the following question: Is evolution even possible in Islamic thought? Given the review provided here, the answer seems to be yes and no, as it significantly depends on one’s metaphysical presuppositions which, in turn, impact how one navigates Islam and evolution. The three thinkers we looked at here – Nasr, Malik, and Guessoum – clearly occupy very different metaphysical frameworks, which results in them occupying different approaches and thus conclusions.

These metaphysical differences will not be dissolving anytime soon. As stated earlier, Islam has many different intellectual camps, with each one having its own intellectual genealogy. Depending on what is adopted and neglected, and how they are applied to the conversation, people may arrive at different conclusions as is seen in this puzzle. Accordingly, the best one can do in such matters is to make their metaphysical commitments apparent and their disagreements with other thinkers explicit. This will help with clearly seeing where everyone stands and simultaneously help with moving the conversation forward.

Bibliography

Al-Ghazālī, Abū Ḥāmid. 2000. The Incoherence of the Philosophers. Translated by Michael E. Marmura. Utah: Brigham University Press.

Bakar, Osman. 1984. “The Nature and Extent of Criticism of Evolutionary Theory.” In Critique of Evolutionary Theory: A Collection of Essays, edited by, Osman Bakar, 123–152. Kuala Lumpur: The Islamic Academy of Science and Nurin Enterprise.

Bigliardi, Stefano. 2014. Islam and the Quest for Modern Science: Conversations with Adnan Oktar, Mehdi Golshani, Mohammed Basil Altaie, Zaghloul El-Naggar, Bruno Guiderdoni and Nidhal Guessoum. Istanbul: The Swedish Research Institute.

Bowler, Peter. 2015. The Mendelian Revolution: The Emergence of Hereditarian Concepts in Modern Science and Society. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Corsi, Pietro. 1988. The Age of Lamarck: Evolutionary Theories in France / 1790-1830. California: The University of California Press.

Guessoum, Nidhal. 2011a. Islam’s Quantum Question: Reconciling Muslim Tradition and Modern Science. London: I.B. Tauris.

Guessoum, Nidhal. 2011b. “Islam and Biological Evolution: Exploring Classical Sources and Methodologies by David Solomon Jalajel.” Journal of Islamic Studies 22: 476–479.

Guessoum, Nidhal. 2016. “Islamic Theological Views on Darwinian Evolution.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Accessed 1st of January 2020. Available at: https:// oxfordre.com/religion/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.001.0001/acrefore9780199340378-e-36

Hasan, Ali. 2013. “Al-Ghazali and Ibn Rushd (Averroes) on Creation and the Divine Attributes.” In Models of God and Alternative Ultimate Realities, edited by Jeanine Diller and Asa Kasher, 141-156. Cham: Springer.

Hassan, Laura. 2020. Ashʿarism Encounters Avicennism: Sayf al-Dīn al-Āmidī on Creation. New Jersey: Georgia Press.

Jackson, Sherman. 2009. Islam and the Problem of Black Suffering. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jalajel, David Solomon. 2009. Islam and Biological Evolution: Exploring Classical Sources and Methodologies. Western Cape: University of the Western Cape.

Jalajel, David Solomon. 2018. “Tawaqquf and Acceptance of Human Evolution.” Yaqeen Institute. Accessed 1st of January 2020. Available at: https://yaqeeninstitute. org/dr-david-solomon-jalajel/tawaqquf-and-acceptance-of-human-evolution/#. Xgw_HxczbPA

Koca, Özgür. 2020. Islam, Causality, and Freedom: From the Medieval to the Modern Era. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Laland, Kevin, Tobias Uller, Marc Feldman, Kim Sterelny, Gerd B. Müller, Armin Moczek, Eva Jablonka, and John Odling-Smee. 2014. “Does Evolutionary Theory Need a Rethink? Yes, Urgently.” Nature 514: 161–164.

Lovejoy, Arthur Oncken. 2009. The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea. New Jersey, NY: Transaction Publishers.

Malik, Shoaib Ahmed. 2021. Islam and Evolution: Al-Ghazālī and the Modern Evolutionary Paradigm. Abingdon: Routledge.

Müller-Wille, S. and Hans-Jörg Rheinberger. 2012. A Cultural History of Heredity. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. 2006. “On the Question of Biological Origins.” Islam and Science 4: 181–197.

Pigliucci, Massimo, and Gerd B. Müller. 2010. Evolution: The Extended Synthesis. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Qadhi, Yasir, and Nazir Khan. 2018. “Human Origins: Theological Conclusions and Empirical Limitations.” Yaqeen Institute. Accessed 19th of August 2020. Available at: https://yaqeeninstitute.org/nazir-khan/human-origins-theological-conclusionsand-empirical-limitations/

Ruse, Michael. 1999. The Darwinian Revolution: Science Red in Tooth and Claw. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Schmidtke, Sabine, ed. 2014. The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Theology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Winter, Timothy, ed. 2008. The Cambridge Companion to Classical Islamic Theology. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Wray, Gregory A., Hopi E. Hoekstra, Douglas J. Futuyma, Richard E. Lenski, Trudy F. C. Mackay, Dolph Schluter, and Joan E. Strassmann. 2014. “Does Evolutionary Theory Need a Rethink? No, All Is Well.” Nature 514: 161–164.

Young, Davis. A. and Ralph F. Stearley. The Bible, Rocks and Time: Geological Evidence for the Age of the Earth. Illinois: IVP Academic.

Notes

[1] For the sake of convenience, Malik subsumed Eve, who is also thought to be created miraculously, under Adamic Exceptionalism.

[2] For simplicity, I define anti-traditionalism as a mode of though which significantly and largely rejects the Islamic intellectual heritage (schools of thought, ideas, and methodologies) in favor of new modes of thinking.

[3] He makes it seem that there are three distinctive ideas in his article, but, on closer inspection, it seems that there are only two.

[4] He demarcates between Western and Islamic societies through which evolution is seen as a Western product.

[5] Elsewhere, Osman Bakar (1984), a student of Nasr’s, better elucidates his paradigm: “A species is an ‘idea’ in the Divine Mind with all its possibilities. It is not an individual reality but an archetype, and as such it lies beyond limitations and beyond change. It is first manifested as individuals belonging to it in the subtle state where each individual reality is constituted by the conjunction of a ‘form’ and a subtle ‘proto-matter,’ this ‘form’ referring to the association of qualities of the species which is therefore the trace of its immutable essence. This means that different types of animals, for example, pre-existed at the level immediately above the corporeal world as non-spatial forms but clothed with a certain ‘matter’ which is of the subtle world. These forms ‘descended’ into the material world, wherever the latter was ready to receive them, and this ‘descent’ had the nature of a sudden coagulation and hence also the nature of a limitation or fragmentation of the original subtle form. Thus species appear on the plane of physical reality by successive ‘manifestations’ or ‘materialisations’ starting from the subtle state. This then is the ‘vertical’ genesis of species of traditional metaphysics as opposed to the ‘horizontal’ genesis of species from a single cell of modern biology.”

[6] Interestingly, Averroes did have his disagreements with al-Ghazālī. See Hasan (2013) for details.

[7] The disagreements between Neo-platonism and Ashʿarism are nothing new. Al-Ghazālī (2000), for instance, is famous for writing The Incoherence of the Philosophers in which he criticises twenty metaphysical propositions of Neo-platonic thought. See Hassan (2020) for more details.

Cite this article

Reply to this Theological Puzzle

Disagree with the conclusions of this puzzle? Did the Author miss something? We encourage readers to reply via a ‘Note’ of up to 2000 words. Notes do not need to follow the puzzle structure. See Contribute for more information. An honorarium may be payable.

Contact the author

Shoaib Malik

Email: [email protected]